So where in the realm was Pepys wandering? Not Wiltshire, that much is certain from his own words. The lofty moors of Cornwall and Devon, perhaps? Remote isles off the Scottish coast? The Lakes or the Peaks?

None of them. He was writing about Kit's Coty, a Neolithic burial chamber in North Kent, part of a cluster of prehistoric monuments known as the Medway Megaliths.

The Megaliths form two distinct groupings on either side of the Medway valley. On the western side, Kit's Coty, Little Kit's Coty/The Countless Stones, the White Horse Stone and the Coffin Stone sit within easy walking distance of each other while on the eastern side, the remnants of two longbarrows lay in close proximity.

Together, they form the only surviving megalithic complex in Eastern England and, although they are all in various states of ruination, their survival in an area of intense agriculture, riverside industrialisation and heavy transport links is remarkable. They can also, provided one is armed with the knowledge of their exact locations, be visited in a single day.

White Horse Stone

From behind the Cossington Services on the southbound A229, a track crosses a bridge over the Eurostar line and follows the Pilgrim's Way toward the North Downs. Between the track and a field can be found the White Horse Stone. There once existed a Lower White Horse Stone to the west, but it was destroyed in 1823 and its site is now covered by the road. When the Eurostar line was constructed, the site of a Neolithic longhouse was excavated at the point where the railway enters a tunnel, and a now lost monument known as Smythe's Megalith - named after a local antiquarian who investigated it in the 1820's - once stood in the field.

A scattering of smaller stones are strewn across the undergrowth immediately to the west of the stone. I suspect that this monument is a collapsed burial chamber, the main relic being a capstone that has been propped onto its side, and the others its supports.

|

| A scattering of stones |

Kit's Coty

Pepys was not the last notable figure to visit this monument, standing on the southern slope of Bluebell Hill with extensive views across the Medway valley. It was sketched in 1722 by the antiquarian William Stukeley, who also noticed a low, 70-yard mound extending to the west... evidence that Kit's Coty formed the entrance chamber of a longbarrow. A rock known as the General's Tombstone stood at the end of this mound, but this was destroyed in 1867 and the remnants of the mound have since been ploughed away.

|

| Stukeley's sketch of 1722 |

|

| Kit's Coty from the NW |

At the bottom of the hill, opposite the entrance to a vineyard, sits my next destination.

Little Kit's Coty/ The Countless Stones

|

The idea that the stones cannot be counted is a familiar motif with Neolithic and Bronze Age sites. Similar legends exist at the Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire and at Long Meg And Her Daughters in Cumbria, to name but two.

|

| Stukeley's sketch proves that the monument was demolished prior to 1722 |

The Coffin Stone

Although a public footpath obliquely traverses the vineyard, direct public access to the Coffin Stone does not exist at the moment, although the landowner hopes to provide access in the future. The uppermost stone was recently placed in its position by the farmer, the original Coffin Stone now underneath. It looks to me very much like a collapsed burial chamber, perhaps very similar to Kit's Coty.

Although the western cluster of Medway Megaliths are only a couple of miles away on the other side of the valley, the River Medway is planted firmly in the way so I have to use my car, making use of the A229 and the M20 as well as a couple of country roads, in order to reach the village of Trottescliffe.

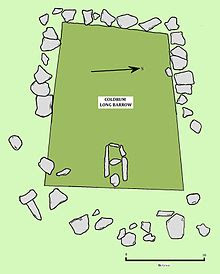

Coldrum Long Barrow

The barrow stands in a pretty spot east of the village, which is pronounced 'Trosley'. It overlooks broad farmland, with the North Downs rising across the fields. As can be seen from the above picture, the stone-built chamber has suffered from slippage, and many of its stones have tumbled down the slope. The mound is surrounded by smaller kerbstones, known as a peristalith, and the spot is popular with practitioners of the Earth Religions - the tree behind the barrow is often festooned with clouties and offerings.

|

| Tumbled stones at the foot of the mound |

Archaeological investigations over a century ago uncovered the remains of seventeen individuals, interred over two occasions during the Early Neolithic, some five thousand years ago. The skeletons showed signs of excarnation and dismemberment before being deposited within the barrow.

|

| Bone assemblage from Coldrum |

Addington Park Longbarrow

|

| Stones from the chamber |

Little more than a mile from Trottecliffe sits the neighbouring village of Addington, which contains the remnants of two Longbarrows. The first, Addington Park, is easy to find as a road originating in the village goes right over the top of it.

|

| The chamber lays north of the road, with peristalith stones visible on both sides |

|

| Perstalith stones south of the road |

This monument is difficult to spot from the road, as it sits in the rear garden of a property called 'Rose Alba'. It is possible to contact the owners and arrange for a guided tour of both Chestnuts and Addington Park, which takes about an hour and involves dowsing.

Archaeological exploration has recovered the remains of nine or ten individuals, although the acidic nature of the sandy soil upon which the monument sits means that quite a lot of organic material may have been destroyed. It was found that deliberate attempts had been made to damage the barrow, probably by zealous Christians - a medieval practice which has damaged many prehistoric monuments in the past, most notably the great complex at Avebury, Wiltshire.

|

| ©Adamsan at Wikipedia |

And for this sightseer, another quest is over. The Medway Megaliths, this scattering of stones across a river valley in the Garden Of England, have been visited in a single afternoon and, as I make my way home in the deepening darkness, I realise that there is, after all, an advantage to living in South Essex.

It's close to Kent!

Previous blog articles that included megalithic monuments:

And The White Horse Looked On

Rough Circles

On Going A Journey